Smishing and vishing are two types of fraud that use SMS (smishing) and voice (vishing) to trick people into giving up money or personal information. These two increasingly common types of “social engineering” attacks have been wreaking havoc worldwide recently—and the change and uncertainty brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated the problem.

This article will:

- Explain what smishing and vishing attacks are and how they relate to phishing

- Provide examples of each type of attack alongside tips on how to identify them

- Explain what you should do if you’re targeted by a smishing or vishing attack

Smishing, vishing, and phishing

Before we look at smishing and vishing in detail, let’s clarify the difference between smishing, vishing, and phishing. Smishing and vishing are two types of phishing attacks. They’re “social engineering attacks,” meaning that in a smishing or vishing attack, the attacker uses impersonation to exploit the target’s trust.

Because 96% of phishing attacks arrive via email, the term “phishing” is sometimes used to refer exclusively to email-based attacks. But it’s important to guard against threats arising from other means of communication too, including smishing, vishing, and social media phishing.

Regardless of how the attack is delivered, the message will appear to come from a trusted sender and may ask the recipient to:

- Follow a link, either to download a file or to submit personal information

- Reply to the message with personal or sensitive information

- Carry out an action such as purchasing vouchers or transferring funds

What is smishing?

-

What is smishing?

Smishing—or “SMS phishing”—is phishing via SMS (text messages). The victim of a smishing attack receives a text message, supposedly from a trusted source, that aims to solicit their personal information.

These messages often contain a link (generally a shortened URL) and, like other phishing attacks, they’ll encourage the recipient to take some “urgent” action, for example:

- Claiming a prize

- Claiming a tax refund

- Confirming and rescheduling a delivery

- Locking their online banking account

Smishing attacks continue to rise

Just like phishing via email, the rates of smishing continue to rise year on year. Data from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) suggests that US consumers lost over $86 million through scam text messages in 2020.

Reports of malicious text messages nearly tripled: from 107,663 in 2019 to 305,241 in 2020. And in October 2021, the UK government relaunched its Joint Fraud Taskforce after research revealed that 82% of adults received a suspicious text or email over the previous three months.

Smishing attacks most commonly target consumers. But increasingly, fraudsters are using smishing techniques to target businesses, too. A good example of how smishing attacks affect businesses comes from the UK, where the country’s tax authority (Her Majesty’s Revenues and Customs or “HMRC”) regularly warns businesses about scam text messages.

In October 2021, HMRC reminded business owners that it would “never ask for personal or financial information” via text and that recipients should never reply to a message offering “a tax refund in exchange for personal or financial details.”

How to identify a smishing attack

Cybercriminals are using increasingly sophisticated methods to make their messages as believable as possible. That’s why many thousands of people fall for smishing scams every year. In a study carried out by Lloyds TSB, participants were shown 20 emails and texts, half of which were inauthentic. Only 18% of participants correctly identified all of the fakes.

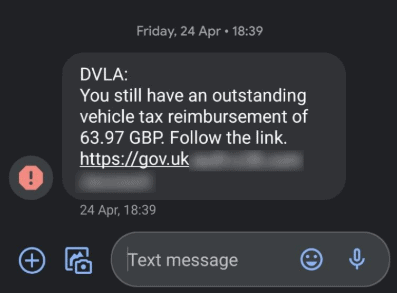

So, given that smishing messages are so persuasive, how can you spot one? To help familiarize you with how smishing messages look, here’s a real-life example:

The message above appears to be from the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) and invites the recipient to visit a link. Note that the link appears to lead to a legitimate website—“gov.uk” is a UK government-owned domain.The use of a legitimate-looking URL is an excellent example of the increasingly sophisticated methods that smishing attackers use to trick unsuspecting people into falling for their scams.

Smishing texts share some common characteristics with phishing emails. For example, a smishing message will normally:

- Convey a sense of urgency

- Contain a link (even if the link appears legitimate, like in the example above)

- Contain a request personal information

Another clue that a text message might be malicious is the sender’s phone number. Large organizations, like banks and retailers, will generally send text messages from short-code numbers. Smishing texts often come from “regular” 11-digit mobile numbers. Smishing messages might also be poorly-written or contain typos. However, don’t rely on these sorts of mistakes—typos in smishing messages are increasingly uncommon as fraudsters become more sophisticated.

What is vishing?

-

What is vishing?

Vishing — or “voice phishing” — is phishing via phone call. Vishing scams commonly use Voice over IP (VoIP) technology.

Like targets of other types of phishing attacks, the victim of a vishing attack will receive a phone call (or a voicemail) from a scammer, pretending to be a trusted person who’s attempting to elicit personal information such as credit card or login details.

So, how do hackers pull this off? They use a range of advanced techniques, including:

- Faking caller ID, so it appears that the call is coming from a trusted number

- Utilizing “war dialers” to call large numbers of people en masse

- Using synthetic speech and automated call processes

A vishing scam often starts with an automated message, telling the recipient that they are the victim of identity fraud. The message requests that the recipient call a specific number. When doing so, they are asked to disclose personal information. Hackers then may use the information themselves to gain access to other accounts or sell the information on the Dark Web.

Vishing attacks and COVID-19

The pandemic has presented many opportunities for online fraud, and we’ve seen COVID–related smishing scams in abundance. Here’s a particularly appalling example—in June 2021, the Better Business Bureau revealed that scammers were impersonating agents from a government-backed funeral program and targeting families that had lost loved ones to coronavirus.

But—like with smishing—vishing scammers don’t just target consumers. COVID-19-related vishing attacks have hit businesses, too.

On August 20, 2020, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) issued a joint statement warning businesses about an ongoing vishing campaign. The agencies warn that cybercriminals have been exploiting remote-working arrangements throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The scam involves spoofing login pages for corporate Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), so as to steal employees’ credentials. These credentials can be used to obtain additional personal information about the employee.

The attackers then use unattributed VoIP numbers to call employees on their personal mobile phones. The attackers pose as IT helpdesk agents and use a fake verification process using stolen credentials to earn the employee’s trust.

How to identify a vishing attack

Vishing attacks share many of the same hallmarks as smishing attacks. In addition to these indicators, we can categorize vishing attacks according to the person the attacker is impersonating:

- Businesses or charities — Such scam calls may inform you that you have won a prize, present you with you an investment opportunity, or attempt to elicit a charitable donation. If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

- Banks — Banking phone scams will usually incite alarm by informing you about suspicious activity on your account. Always remember that banks will never ask you to confirm your full card number over the phone.

- Government institutions — These calls may claim that you are owed a tax refund or required to pay a fine. They may even threaten legal action if you do not respond.

- Tech support — Posing as an IT technician, an attacker may claim your computer is infected with a virus. You may be asked to download software (which will usually be some form of malware or spyware) or allow the attacker to take remote control of your computer.

How to prevent smishing and vishing attacks

One key to preventing smishing and vishing attacks is providing employees with security training. Security awareness training is a key part of complying with privacy and security laws, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the New York SHIELD Act. You can read more about how compliance standards affect cybersecurity on our compliance hub.

Training can help ensure all employees are familiar with the common signs of smishing and vishing attacks, which could reduce the possibility of falling victim to such an attack. But, what do you do if you receive a suspicious SMS or voice message? The first rule is: don’t respond.

If you receive a text requesting that you follow a link—or a phone message requesting that you call a number or divulge personal information—ignore it until you’ve confirmed whether or not it’s legitimate. If the message appears to be from a trusted institution, search for the organization’s phone number and call directly. For example, if a message appears to be from your phone provider, search for your phone provider’s customer service number and discuss the request directly with the operator.

If you receive a vishing or smishing message at work or on a work device, make sure you report it to your IT or security team. If you’re on a personal device, you should report significant smishing and vishing attacks to the relevant authorities in your country, such as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) or Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

For more tips on how to identify and prevent phishing attacks, including vishing and smishing, follow Tessian on LinkedIn or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.